|

Very

high-temperature impact melt products as evidence for cosmic airbursts and

impacts 12,900 years ago Ted E. Bunch, Robert E. Hermes, Andrew M.T. Moore, Douglas J. Kennett,

James C. Weaver, James H. Wittke, Paul S. DeCarli, James L.

Bischoff, Gordon C. Hillman, George A. Howard, David R. Kimbel,

Gunther Kletetschka, Carl P. Lipo, Sachiko Sakai, Zsolt Revay,

Allen West, Richard B. Firestone, and James P. Kennett PNAS July 10, 2012. 109 (28) E1903-E1912; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1204453109 Abstract It has been proposed that fragments of an asteroid or comet impacted

Earth, deposited silica-and iron-rich microspherules and other

proxies across several continents, and triggered the Younger Dryas

cooling episode 12,900 years ago. Although many independent groups have

confirmed the impact evidence, the hypothesis remains controversial because

some groups have failed to do so. We examined sediment sequences from 18

dated Younger Dryas boundary (YDB) sites across three continents (North

America, Europe, and Asia), spanning 12,000 km around nearly one-third of

the planet. All sites display abundant microspherules in the YDB

with none or few above and below. In addition, three sites (Abu Hureyra,

Syria; Melrose, Pennsylvania; and Blackville, South Carolina) display

vesicular, high-temperature, siliceous scoria-like objects, or SLOs, that

match the spherules geochemically. We compared YDB objects with melt products

from a known cosmic impact (Meteor Crater, Arizona) and from the 1945 Trinity

nuclear airburst in Socorro, New Mexico, and found that all of these high-energy

events produced material that is geochemically and morphologically

comparable, including: (i) high-temperature, rapidly quenched microspherules and

SLOs; (ii) corundum, mullite, and suessite (Fe3Si), a rare meteoritic mineral that forms under high temperatures; (iii)

melted SiO2 glass, or lechatelierite, with flow textures (or schlieren) that

form at > 2,200 °C; and (iv) particles with features

indicative of high-energy interparticle collisions. These results are

inconsistent with anthropogenic, volcanic, authigenic, and cosmic materials,

yet consistent with cosmic ejecta, supporting the hypothesis of

extraterrestrial airbursts/impacts 12,900 years ago. The wide geographic

distribution of SLOs is consistent with multiple impactors. · tektite · microcraters · oxygen fugacity · trinitite Manuscript Text The discovery of anomalous materials in a thin sedimentary layer up to a

few cm thick and broadly distributed across several continents led Firestone

et al. (1)

to propose that a cosmic impact (note that “impact” denotes a collision by a

cosmic object either with Earth’s surface, producing a crater, or with its

atmosphere, producing an airburst) occurred at 12.9 kiloannum (ka;

all dates are in calendar or calibrated ka, unless otherwise indicated) near

the onset of the Younger Dryas (YD) cooling episode. This stratum, called the

YD boundary layer, or YDB, often occurs directly beneath an organic-rich

layer, referred to as a black mat (2),

that is distributed widely over North America and parts of South America,

Europe, and Syria. Black mats also occur less frequently in quaternary

deposits that are younger and older than 12.9 ka (2).

The YDB layer contains elevated abundances of iron- and silica-rich microspherules (collectively

called “spherules”) that are interpreted to have originated by cosmic impact

because of their unique properties, as discussed below. Other markers include

sediment and magnetic grains with elevated iridium concentrations and exotic

carbon forms, such as nanodiamonds, glass-like carbon, aciniform soot,

fullerenes, carbon onions, and carbon spherules (3, 4).

The Greenland Ice Sheet also contains high concentrations of atmospheric

ammonium and nitrates at 12.9 ka, indicative of biomass burning at the

YD onset and/or high-temperature, impact-related chemical synthesis (5).

Although these proxies are not unique to the YDB layer, the combined

assemblage is highly unusual because these YDB markers are typically present

in abundances that are substantially above background, and the assemblage

serves as a datum layer for the YD onset at 12.9 ka. The wide range of

proxies is considered here to represent evidence for a cosmic impact that

caused airbursts/impacts (the YDB event may have produced ground impacts and

atmospheric airbursts) across several continents. Since the publication of Firestone et al. (1),

numerous independent researchers have undertaken to replicate the results.

Two groups were unable to confirm YDB peaks in spherules (6, 7),

whereas seven other groups have confirmed them (*, †, ‡, 8⇓⇓⇓⇓⇓–14),

with most but not all agreeing that their evidence is consistent with a

cosmic impact. Of these workers, Fayek et al. (8)

initially observed nonspherulitic melted glass in the well-dated

YDB layer at Murray Springs, Arizona, reporting “iron oxide spherules

(framboids) in a glassy iron–silica matrix, which is one indicator of a

possible meteorite impact…. Such a high formation temperature is only

consistent with impact… conditions.” Similar materials were found in the YDB

layer in Venezuela by Mahaney et al. (12),

who observed “welded microspherules,… brecciated/impacted quartz and

feldspar grains, fused metallic Fe and Al, and… aluminosilicate glass,” all

of which are consistent with a cosmic impact. Proxies in High-Temperature Impact Plumes. Firestone et al. (1)

proposed that YDB microspherules resulted from ablation of the

impactor and/or from high-temperature, impact-related melting of terrestrial

target rocks. In this paper, we explore evidence for the latter possibility.

Such an extraterrestrial (ET) impact event produces a turbulent impact plume

or fireball cloud containing vapor, melted rock, shocked and unshocked rock

debris, breccias, microspherules, and other target and impactor

materials. One of the most prominent impact materials is melted siliceous

glass (lechatelierite), which forms within the impact plume at temperatures

of up to 2,200 °C, the boiling point of quartz. Lechatelierite cannot

be produced volcanically, but can form during lightning strikes as

distinctive melt products called fulgurites that typically have unique

tubular morphologies (15).

It is also common in cratering events, such as Meteor Crater, AZ (16),

and Haughton Crater, Canada§, as well as in probable high-temperature aerial

bursts that produced melt rocks, such as Australasian tektites (17),

Libyan Desert Glass (LDG) (17), Dakhleh Glass

(18),

and potential, but unconfirmed, melt glass from Tunguska, Siberia (19).

Similar lechatelierite-rich material formed in the Trinity nuclear

detonation, in which surface materials were drawn up and melted within the

plume (20). After the formation of an impact fireball, convective cells form at

temperatures higher than at the surface of the sun (> 4,700 °C),

and materials in these cells interact during the short lifetime of the plume.

Some cells will contain solidified or still-plastic impactites, whereas in

other cells, the material remains molten. Some impactites are rapidly ejected

from the plume to form proximal and distal ejecta depending on their mass and

velocity, whereas others are drawn into the denser parts of the plume, where

they may collide repeatedly, producing multiple accretionary and collisional

features. Some features, such as microcraters, are unique to impacts and

cosmic ablation and do not result from volcanic or anthropogenic processes¶. For ground impacts, such as Meteor Crater (16),

most melting occurred during the formation of the crater. Some of the molten

rock was ejected at high angles, subsequently interacting with the rising hot

gas/particulate cloud. Most of this material ultimately fell back onto the

rim as proximal ejecta, and molten material ejected at lower angles became

distal ejecta. Cosmic impacts also include atmospheric impacts called

airbursts, which produce some material that is similar to that

produced in a ground impact. Aerial bursts differ from ground impacts in that

mechanically shocked rocks are not formed, and impact markers are primarily

limited to materials melted on the surface or within the plume. Glassy

spherules and angular melted objects also are produced by the hot

hypervelocity jet descending to the ground from the atmospheric explosion.

The coupling of the airburst fireball with the upper soil layer of Earth’s

surface causes major melting of material to a depth of a few cm. Svetsov and

Wasson (2007) ∥ calculated

that the thickness of the melted layer was a function of time and flux

density, so that for Te > 4,700 °C

at a duration of several seconds, the thickness of melt is 1–1.5 cm.

Calculations show that for higher fluxes, more soil is melted, forming

thicker layers, as exemplified by Australasian tektite layered melts. The results of an aerial detonation of an atomic bomb are similar to

those of a cosmic airburst (e.g., lofting, mixing, collisions, and

entrainment), although the method of heating is somewhat different because of

radioactive byproducts (SI Appendix).

The first atomic airburst occurred atop a 30-m tower at the Alamogordo

Bombing Range, New Mexico, in 1945, and on detonation, the thermal blast wave

melted 1–3 cm of the desert soils up to approximately 150 m in

radius. The blast did not form a typical impact-type crater; instead, the

shock wave excavated a shallow depression 1.4 m deep and 80 m in

diameter, lifting molten and unmelted material into the rising, hot

detonation plume. Other melted material was ejected at lower angles, forming

distal ejecta. For Trinity, Hermes and Strickfaden (20)

estimated an average plume temperature of 8,000 °C at a duration of

3 s and an energy yield of up to 18 kilotons (kt) trinitrotoluene

(TNT) equivalent. Fallback of the molten material, referred to as trinitite,

littered the surface for a diameter of 600 m, in some places forming

green glass puddles (similar to Australasian layered tektites). The

ejecta includes irregularly shaped fragments and aerodynamically shaped

teardrops, beads, and dumbbell glasses, many of which show collision and

accretion features resulting from interactions in the plume (similar to Australasian

splash-form tektites). These results are identical to those from known cosmic

airbursts. SI Appendix,

Table S1 provide a comparison of YDB objects with impact

products from Meteor Crater, the Australasian tektite field, and the Trinity

nuclear airburst. Scope of Study. We investigated YDB markers at 18 dated sites, spanning 12,000 km

across seven countries on three continents (SI Appendix, Fig. S1),

greatly expanding the extent of the YDB marker field beyond earlier studies (1).

Currently, there are no known limits to the field. Using both deductive and

inductive approaches, we searched for and analyzed YDB spherules and melted

siliceous glass, called scoria-like objects (SLOs), both referred to below as

YDB objects. The YDB layer at all 18 sites contains microspherules, but

SLOs were found at only three sites: Blackville, South Carolina; Abu Hureyra,

Syria; and Melrose, Pennsylvania. Here, we focus primarily on abundances,

morphology, and geochemistry of the YDB SLOs. Secondarily, we discuss

YDB microspherules with regard to their geochemical similarity

and co-occurrence with SLOs. We also compare compositions of YDB objects to

compositions: (i) of materials resulting from meteoritic ablation and

from terrestrial processes, such as volcanism, anthropogenesis, and

geological processes; and (ii) from Meteor Crater, the Trinity nuclear

detonation, and four ET aerial bursts at Tunguska, Siberia; Dakhleh Oasis,

Egypt; Libyan Desert Glass Field, Egypt; and the Australasian tektite strewnfield,

SE Asia. For any investigation into the origin of YDB objects, the question arises

as to whether these objects formed by cosmic impact or by some other process.

This is crucial, because sedimentary spherules are found throughout the

geological record and can result from nonimpact processes, such as cosmic

influx, meteoritic ablation, anthropogenesis, lightning, and volcanism.

However, although microspherules with widely varying origins can

appear superficially similar, their origins may be determined with reasonably

high confidence by a combination of various analyses—e.g., scanning electron

microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and wavelength-dispersive

spectroscopy (WDS) by electron microprobe—to examine evidence for microcratering,

dendritic surface patterns produced during rapid melting—quenching **, and

geochemical composition. Results and discussion are below and in the SI Appendix. SLOs at YDB Sites. Abu Hureyra, Syria. This is one of a few archaeological sites that record the transition from

nomadic hunter—gatherers to farmer—hunters living in permanent villages (21).

Occupied from the late Epipalaeolithic through the Early Neolithic

(13.4–7.5 ka), the site is located close to the Euphrates River on

well-developed, highly calcareous soils containing platy flint (chert)

fragments, and the regional valley sides are composed of chalk with thin beds

of very fine-grained flint. The dominant lithology is limestone within a few

km, whereas gypsum deposits are prominent 40 km away, and basalt is

found 80 km distant. Much of this part of northern Syria consists of

highly calcareous Mediterranean, steppe, and desert soils. To the east of

Abu Hureyra, there are desert soils marked by wind-polished flint

fragments forming a pediment on top of marls (calcareous and clayey

mudstones). Thus, surface sediments and rocks of the entire region are

enriched in CaO and SiO2. Moore and co-workers

excavated the site in 1972 and 1973, and obtained 13 radiocarbon dates

ranging from 13.37 ± 0.30 to 9.26 ± 0.13 cal ka

B.P., including five that ranged from 13.04 ± 0.15 to

12.78 ± 0.14 ka, crossing the YDB interval (21)

(SI Appendix,

Table S2). Linear interpolation places the date of the YDB

layer at 12.9 ± 0.2 ka (1σ probability) at a

depth of 3.6 m below surface (mbs) at 284.7 m above sea level

(m asl) (SI Appendix,

Figs. S2D and S3). The location of the YDB

layer is further supported by evidence of 12.9-ka climatic cooling and drying

based on the palynological and macrobotanical record that reveal a

sudden decline of 60–100% in the abundance of charred seed remains of several

major groups of food plants from Abu Hureyra. Altogether, more than 150

species of plants showed the distinct effects of the transition from warmer,

moister conditions during the Bølling-Allerød (14.5–12.9 ka)

to cooler, dryer condition during the Younger Dryas (12.9–11.5 ka). Blackville, South Carolina. This dated site is in the rim of a Carolina Bay, one of a group of

> 50,000 elliptical and often overlapping depressions with raised

rims scattered across the Atlantic Coastal Plain from New Jersey to Alabama (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

For this study, samples were cored by hand auger at the thickest

part of the bay rim, raised 2 m above the surrounding terrain. The

sediment sequence is represented by eolian and alluvial sediments composed of

variable loamy to silty red clays down to an apparent unconformity at

190 cm below surface (cmbs). Below this there is massive, variegated red

clay, interpreted as a paleosol predating bay rim formation (Miocene marine

clay > 1 million years old) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

A peak in both SLOs and spherules occurs in a 15 cm—thick interval

beginning at 190 cmbs above the clay section, extending up to

175 cmbs (SI Appendix,

Table S3). Three optically stimulated luminescence (OSL)

dates were obtained at 183, 152, and 107 cmbs, and the OSL date of

12.96 ± 1.2 ka in the proxy-rich layer at 183 cmbs is

consistent with Firestone et al. (1)

(SI Appendix, Fig. S4

and Table S2). Melrose, Pennsylvania. During the Last Glacial Maximum, the Melrose area in NE Pennsylvania lay

beneath 0.5–1 km of glacial ice, which began to retreat rapidly after

18 ka (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Continuous samples were taken from the surface to a depth of 48 cmbs,

and the sedimentary profile consists of fine-grained, humic colluvium

down to 38 cmbs, resting on sharply defined end-Pleistocene glacial till

(diamicton), containing 40 wt% angular clasts > 2 mm in

diameter. Major abundance peaks in SLOs and spherules were encountered above

the till at a depth of 15–28 cmbs, consistent with emplacement after

18 ka. An OSL date was acquired at 28 cmbs, yielding an age of

16.4 ± 1.6 ka, and, assuming a modern age for the surface

layer, linear interpolation dates the proxy-rich YDB layer at a depth of

21 cmbs to 12.9 ± 1.6 ka (SI Appendix, Fig. S5

and Table S2). YDB sites lacking SLOs. The other 15 sites, displaying spherules but no SLOs, are distributed

across six countries on three continents, representing a wide range of

climatic regimes, biomes, depositional environments, sediment compositions,

elevations (2–1,833 m), and depths to the YDB layer

(13 cm–14.0 m) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

YDB spherules and other proxies have been previously reported at seven of the

18 sites (1).

The 12.9-ka YDB layers were dated using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS)

radiocarbon dating, OSL, and/or thermal luminescence (TL). Results and Discussion Impact-Related Spherules Description. The YDB layer at 18 sites displays peaks in Fe-and/or Si-rich magnetic

spherules that usually appear as highly reflective, black-to-clear spheroids

(Fig. 1 and SI Appendix,

Fig. S6 A–C), although 10%

display more complex shapes, including teardrops and dumbbells (SI AppendixFig. S6 D–H).

Spherules range from 10 μm to 5.5 mm in diameter (mean,

240 μm; median, 40 μm), and concentrations range from

5–4,900 spherules/kg (mean, 940/kg; median, 180/kg) (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix,

Table S3). Above and below the YDB layer, concentrations are

zero to low. SEM imaging reveals that the outer surfaces of most spherules

exhibit distinctive skeletal (or dendritic) textures indicative of rapid

quenching producing varying levels of coarseness (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

This texture makes them easily distinguishable from detrital magnetite, which

is typically fine-grained and monocrystalline, and from framboidal grains,

which are rounded aggregates of blocky crystals. It is crucial to note that

these other types of grains cannot be easily differentiated from impact

spherules by light microscopy and instead require investigation by SEM.

Textures and morphologies of YDB spherules correspond to those observed in

known impact events, such as at the 65-million-year-old Cretaceous—Paleogene

boundary, the 50-ka Meteor Crater impact, and the Tunguska airburst in 1908 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Fig. 1. Light photomicrographs of YDB objects. (Upper) SLOs and (Lower)

magnetic spherules. A = Abu Hureyra, B = Blackville, M = Melrose. Fig. 2. Site graphs for three key sites. SLOs and microspherules exhibit

significant peaks in YDB layer. Depth is relative to YDB layer, represented

by the light blue bar. SLOs Description. Three sites contained conspicuous assemblages of both spherules and SLOs

that are composed of shock-fused vesicular siliceous glass, texturally similar

to volcanic scoria. Most SLOs are irregularly shaped, although

frequently they are composed of several fused, subroundedglassy objects.

As compared to spherules, most SLOs contain higher concentrations of Si, Al,

and Ca, along with lower Fe, and they rarely display the dendritic textures

characteristic of most Fe-rich spherules. They are nearly identical in shape

and texture to high-temperature materials from the Trinity nuclear

detonation, Meteor Crater, and other impact craters (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Like spherules, SLOs are generally dark brown, black, green, or white, and

may be clear, translucent, or opaque. They are commonly larger than

spherules, ranging from 300 μm to 5.5 mm long (mean,

1.8 mm; median, 1.4 mm) with abundances ranging from

0.06–15.76 g/kg for the magnetic fraction that is > 250 μm.

At the three sites, spherules and SLOs co-occur in the YDB layer dating to

12.9 ka. Concentrations are low to zero above and below the YDB layer. Geochemistry of YDB Objects. Comparison to cosmic spherules and micrometeorites. We compared Mg, total Fe, and Al abundances for 70 SLOs and 340 spherules

with > 700 cosmic spherules and micrometeorites from 83 sites, mostly

in Antarctica and Greenland (Fig. 3A).

Glassy Si-rich extraterrestrial material typically exhibits MgO enrichment of

17× (avg 25 wt%) (23)

relative to YDB spherules and SLOs from all sites (avg 1.7 wt%), the

same as YDB magnetic grains (avg 1.7 wt%). For Al2O3content, extraterrestrial material is depleted 3× (avg 2.7 wt%)

relative to YDB spherules and SLOs from all sites (avg 9.2 wt%), as well

as YDB magnetic grains (avg 9.2 wt%). These results indicate

> 90% of YDB objects are geochemically distinct from cosmic material. Fig. 3. Ternary diagrams comparing molar oxide wt% of YDB SLOs (dark orange)

and magnetic spherules (orange) to (A) cosmic material, (B)

anthropogenic material, and (C) volcanic material. (D) Inferred

temperatures of YDB objects, ranging up to 1,800 °C. Spherules and SLOs

are compositionally similar; both are dissimilar to cosmic, anthropogenic,

and volcanic materials. Comparison to anthropogenic materials. We also compared the compositions of the YDB objects to > 270

anthropogenic spherules and fly ash collected from 48 sites in 28 countries

on five continents (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix,

Table S5), primarily produced by one of the most prolific

sources of atmospheric contamination: coal-fired power plants (24).

The fly ash is 3× enriched in Al2O3 (avg 25.8 wt%) relative to YDB objects and magnetic grains

(avg 9.1 wt%) and depleted 2.5× in P2O5 (0.55 vs. 1.39 wt%, respectively). The result is that 75% of

YDB objects have compositions different from anthropogenic objects.

Furthermore, the potential for anthropogenic contamination is unlikely for

YDB sites, because most are buried 2–14 mbs. Comparison to volcanic glasses. We compared YDB objects with > 10,000 volcanic samples (glass,

tephra, and spherules) from 205 sites in four oceans and on four continents (SI Appendix,

Table S5). Volcanic material is enriched 2× in the alkalis,

Na2O + K2O (avg 3 wt%),

compared with YDB objects (avg 1.5 wt%) and magnetic grains (avg

1.2 wt%). Also, the Fe concentrations for YDB objects (avg 55 wt%)

are enriched 5.5× compared to volcanic material (avg 10 wt%) (Fig. 3C),

which tends to be silica-rich (> 40 wt%) with lower Fe.

Approximately 85% of YDB objects exhibit compositions dissimilar to

silica-rich volcanic material. Furthermore, the YDB assemblages lack typical

volcanic markers, including volcanic ash and tephra. Melt temperatures. A FeOT–Al2O3–SiO2 phase diagram reveals three general groups of YDB objects (Fig. 3D).

A Fe-rich group, dominated by the mineral magnetite, forms at temperatures of

approximately 1,200–1,700 °C. The high-Si/low-Al group is dominated by

quartz, plagioclase, and orthoclase and has liquidus temperatures of

1,200–1,700 °C. An Al—Si-rich group is dominated by mullite and

corundum with liquidus temperatures of 1,400–2,050 °C. Because YDB

objects contain more than the three oxides shown, potentially including H2O, and are not in equilibrium, the liquidus temperatures are almost

certainly lower than indicated. On the other hand, in order for high-silica

material to produce low-viscosity flow bands (schlieren), as observed in many

SLOs, final temperatures of > 2,200 °C are probable, thus

eliminating normal terrestrial processes. Additional temperatures diagrams

are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9. Comparison to impact-related materials. Geochemical compositions of YDB objects are presented in a AI2O3 - CaO - FeOT ternary diagram used to plot compositional variability in

metamorphic rocks (Fig. 4A).

The diagram demonstrates that the composition of YDB objects is

heterogeneous, spanning all metamorphic rock types (including pelitic, quartzofeldspathic,

basic, and calcareous). From 12 craters and tektite strewnfields on

six continents, we compiled compositions of > 1,000 impact-related

markers (spherules, ejecta, and tektites, which are melted glassy objects),

as well as 40 samples of melted terrestrial sediments from two nuclear aerial

detonations: Trinity (22)

and Yucca Flat (25)

(Fig. 4B and SI Appendix,

Table S5). The compositions of YDB impact markers are

heterogeneous, corresponding well with heterogeneous nuclear melt material

and impact proxies. Fig. 4. Compositional ternary diagrams. (A) YDB objects: Spherules

(orange) and SLOs (dark orange) are heterogeneous. Letters indicate plot

areas typical of specific metamorphic rock types: P = pelitic (e.g.,

clayey mudstones and shales), Q = quartzofeldspathic (e.g.,

gneiss and schist), B = basic (e.g., amphibolite), and

C = calcareous (e.g., marble) (40).

(B) Cosmic impact materials in red (N > 1,000)

with nuclear material in light red. (C) Surface sediments, such as

clay, silt, and mud (41).

(D) Metamorphic rocks. Formula for diagrams: A = (Al2O3 + Fe2O3)-(Na2O + K2O); C = [CaO-(3.33 × P2O5)]; F = (FeO + MgO + MnO). Comparison to terrestrial sediments. We also used the acriflavine system to analyze > 1,000 samples of

bulk surface sediment, such as clay, mud, and shale, and a wide range of

terrestrial metamorphic rocks. YDB objects (Fig. 4A)

are similar in composition to surface sediments, such as clay, silt, and mud

(25)

(Fig. 4C),

and to metamorphic rocks, including mudstone, schist, and gneiss (25)

(Fig. 4D). In addition, rare earth element (REE) compositions of the YDB objects

acquired by instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) and prompt gamma

activation analysis (PGAA) are similar to bulk crust and compositions from

several types of tektites, composed of melted terrestrial sediments (SI Appendix,

Fig. S10A). In contrast, REE compositions differ

from those of chondritic meteorites, further confirming that YDB objects are

not typical cosmic material. Furthermore, relative abundances of La, Th, and

Sc confirm that the material is not meteoritic, but rather is of terrestrial

origin (SI Appendix,

Fig. S10B). Likewise, Ni and Cr concentrations in

YDB objects are generally unlike those of chondrites and iron meteorites, but

are an excellent match for terrestrial materials (SI Appendix,

Fig. S10C). Overall, these results indicate SLOs

and spherules are terrestrial in origin, rather than extraterrestrial, and

closely match known cosmic impact material formed from terrestrial sediments. We investigated whether SLOs formed from local or nonlocal material.

Using SEM-EDS percentages of nine major oxides (97 wt%, total) for

Abu Hureyra, Blackville, and Melrose, we compared SLOs to the

composition of local bulk sediments, acquired with NAA and PGAA (SI Appendix,

Table S4). The results for each site show little significant

difference between SLOs and bulk sediment (SI Appendix,

Fig. S11), consistent with the hypothesis that SLOs are

melted local sediment. The results demonstrate that SLOs from Blackville and

Melrose are geochemically similar, but are distinct from SLOs at Abu Hureyra,

suggesting that there are at least two sources of melted terrestrial material

for SLOs (i.e., two different impacts/airbursts). We also performed comparative analyses of the YDB object dataset

demonstrating that: (i) proxy composition is similar regardless of

geographical location (North America vs. Europe vs. Asia); (ii)

compositions are unaffected by method of analysis (SEM-EDS vs. INAA/PGAA);

and (iii) compositions are comparable regardless of the method of

preparation (sectioned vs. whole) (SI Appendix,

Fig. S12). Importance of Melted Silica Glass. Lechatelierite is only known to occur as a product of impact events,

nuclear detonations, and lightning strikes (15).

We observed it in spherules and SLOs from Abu Hureyra, Blackville, and

Melrose (Fig. 5),

suggesting an origin by one of those causes. Lechatelierite is found in

material from Meteor Crater (16),

Haughton Crater, the Australasian tektite field (17), Dakhleh Oasis

(18),

and the Libyan Desert Glass Field (17),

having been produced from whole-rock melting of quartzite, sandstones,

quartz-rich igneous and metamorphic rocks, and/or loess-like materials. The

consensus is that melting begins above 1,700 °C and proceeds to

temperatures > 2,200 °C, the boiling point of quartz, within a

time span of a few seconds depending on the magnitude of the event (26, 27).

These temperatures restrict potential formation processes, because these are

far higher than peak temperatures observed in magmatic eruptions of

< 1,300 °C (28),

wildfires at < 1,454 °C (29),

fired soils at < 1,500 °C (30),

glassy slag from natural biomass combustion at < 1,290 °C (31),

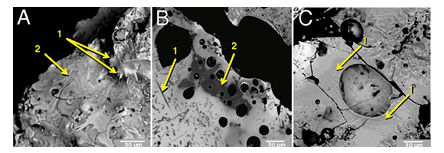

and coal seam fires at < 1,650 °C (31). Fig. 5. SEM-BSE images of high-temperature SLOs with lechatelierite. (A)

Abu Hureyra: portion of a dense 4-mm chunk of lechatelierite. Arrows

identify tacky, viscous protrusions (no. 1) and high-temperature flow lines

or schlieren (no. 2). (B) Blackville: Polished section of SLO displays

vesicles, needle-like mullite quench crystals (no. 1), and dark grey

lechatelierite (no. 2). (C) Melrose: Polished section of a teardrop

displays vesicles and lechatelierite with numerous schlieren (no. 1). Lechatelierite is also common in high-temperature, lightning-produced

fulgurites, of which there are two types (for detailed discussion, see SI Appendix).

First, subsurface fulgurites are glassy tube-like objects (usually

< 2 cm in diameter) formed from melted sediment at > 2,300 °C.

Second, exogenic fulgurites include vesicular glassy spherules, droplets, and

teardrops (usually < 5 cm in diameter) that are only rarely

ejected during the formation of subsurface fulgurites. Both types closely

resemble melted material from cosmic impact events and nuclear airbursts, but

there are recognizable differences: (i) no collisions (fulgurites show

no high-velocity collisional damage by other particles, unlike YDB SLOs and

trinitite); (ii) different ultrastructure (subsurface fulgurites are

tube-like, and broken pieces typically have highly reflective inner surfaces

with sand-coated exterior surfaces, an ultrastructure unlike that of any

known YDB SLO): (iii) lateral distribution (exogenic fulgurites are

typically found < 1 m from the point of a lightning strike,

whereas the known lateral distribution of impact-related SLOs is 4.5 m

at Abu Hureyra, 10 m at Blackville, and 28 m at Melrose); and

(iv) rarity (at 18 sites investigated, some spanning

> 16,000 years, we did not observe any fulgurites or fragments

in any stratum). Pigati et al. (14)

confirmed the presence of YDB spherules and iridium at Murray Springs, AZ,

but proposed that cosmic, volcanic, and impact melt products have been

concentrated over time beneath black mats and in deflational basins,

such as are present at eight of our sites that have wetland-derived black

mats. In this study, we did not observe any fulguritic glass or YDB

SLOs beneath any wetland black mats, contradicting Pigati et al.,

who propose that they should concentrate such materials. We further note that

the enrichment in spherules reported by Pigati et al. at four

non-YDB sites in Chile are most likely caused by volcanism, because their

collection sites are located 20–80 km downslope from 22 major active

volcanoes in the Andes (14).

That group performed no SEM or EDS analyses to determine whether their

spherules are volcanic, cosmic, or impact-related, as stipulated by Firestone

et al. (1)

and Israde-Alcántara et al. (4) Pre-Industrial anthropogenic activities can be eliminated as a source of

lechatelierite because temperatures are too low to melt pure SiO2 at > 1,700 °C. For example, pottery-making began at

approximately 14 ka but maximum temperatures were

< 1,050 °C (31);

glass-making at 5 ka was at < 1,100 °C (32)

and copper-smelting at 7 ka was at < 1,100 °C (32).

Humans have only been able to produce temperatures > 1,700 °C

since the early 20th century in electric-arc furnaces. Only a cosmic impact

event could plausibly have produced the lechatelierite contained in deeply

buried sediments that are 12.9 kiloyears (kyrs) old. SiO2 glass exhibits very high viscosity even at melt temperatures of

> 1,700 °C, and flow textures are thus difficult to produce

until temperatures rise much higher. For example, Wasson and Moore (33)

noted the morphological similarity between Australasian tektites and LDG, and

therefore proposed the formation of LDG by a cosmic aerial burst. They

calculated that for low-viscosity flow of SiO2 to have occurred in Australasian tektites and LDG samples,

temperatures of 2,500–2,700 °C were required. For tektites with lower

SiO2 content, requisite minimum temperatures for flow production may

have been closer to 2,100–2,200 °C. Lechatelierite may form schlieren

in mixed glasses (27)

when viscosity is low enough. Such flow bands are observed in SLOs from

Abu Hureyra and Melrose (Fig. 5)

and if the model of Wasson and Moore (33)

is correct, then an airburst/impact at the YDB produced high-temperature

melting followed by rapid quenching (15).

Extreme temperatures in impact materials are corroborated by the

identification of frothy lechatelierite in Muong Nong tektites

reported by Walter (34),

who proposed that some lechatelierite cores displayed those features because

of the boiling of quartz at 2,200 °C. We surveyed several hundred such

lechatelierite grains in 18 Muong Nong tektites and found similar

evidence of boiling; most samples retained outlines of the precursor quartz

grains (SI Appendix,

Fig. S13). To summarize the evidence, only two natural processes can form

lechatelierite: cosmic impacts and lightning strikes. Based on the evidence,

we conclude that YDB glasses are not fulgurites. Their most plausible origin

is by cosmic impact. Collision and Accretion Features. Evidence for interparticle collisions is observed in YDB samples from

Abu Hureyra, Blackville, and Melrose. These highly diagnostic features

occur within an impact plume when melt droplets, rock particles, dust, and

partially melted debris collide at widely differing relative velocities. Such

features are only known to occur during high-energy atomic detonations and

cosmic impacts, and, because differential velocities are too low ††, have never been reported to have been caused by

volcanism, lightning, or anthropogenic processes. High-speed collisions can

be either constructive, whereby partially molten, plastic spherules grow by

the accretion of smaller melt droplets (35),

or destructive, whereby collisions result in either annihilation of spherules

or surface scarring, leaving small craters (36).

In destructive collisions, small objects commonly display three types of

collisions (36):

(i) microcraters that display brittle fracturing; (ii)

lower-velocity craters that are often elongated, along with very low-impact

“furrows” resulting from oblique impacts (Fig. 6);

and (iii) penetrating collisions between particles that result in

melting and deformational damage (Fig. 7).

Such destructive damage can occur between impactors of the same or different

sizes and compositions, such as carbon impactors colliding with Fe-rich

spherules (SI Appendix,

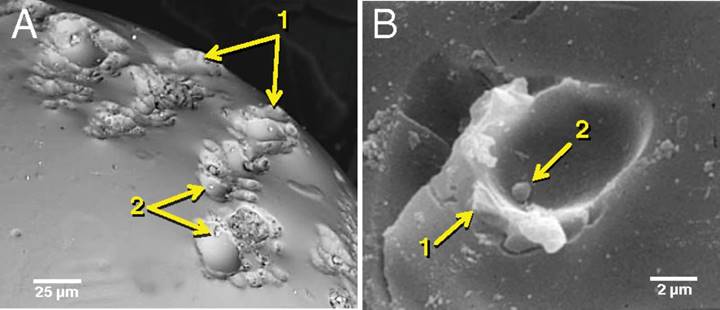

Fig. S14). Fig. 6. SEM-BSE images of impact pitting. (A) Melrose: cluster of oblique

impacts on a SLO that produced raised rims (no. 1). Tiny spherules formed in

most impact pits together with irregularly shaped impact debris (no. 2). (B)

Australasian tektite: Oblique impact produced a raised rim (no. 1). A tiny

spherule is in the crater bottom (no. 2) (36). Fig. 7. SEM-BSE images of collisional spherules. (A) Lake Cuitzeo,

Mexico: collision of two spherules at approximately tens of m/s;

left spherule underwent plastic compaction to form compression rings (nos. 1

and 2), a line of gas vesicles (no. 3), and a splash apron (no. 4). (B) KimbelBay:

Collision of two spherules destroyed one spherule (no. 1) and formed a splash

apron on the other (no. 2). This destructive collision suggests high

differential velocities of tens to hundreds of m/s. Collisions become constructive, or accretionary, at very low velocities

and show characteristics ranging from disrupted projectiles to partial burial

and/or flattening of projectiles on the accreting host (Fig. 8 A and B).

The least energetic accretions are marked by gentle welding together of tacky

projectiles. Accretionary impacts are the most common type observed in 36

glassy impactites from Meteor Crater and in YDB spherules and SLOs (examples

in Fig. 9).

Other types of accretion, such as irregular melt drapings and filament

splatter (37),

are common on YDB objects and melt products from Meteor Crater (Fig. 9D).

Additional examples of collisions and splash forms are shown in SI Appendix,

Fig. S15. This collective evidence is too energetic to be

consistent with any known terrestrial mechanism and is unique to high-energy

cosmic impact events. Fig. 8. SEM-BSE images of accretionary features. (A) Melrose: lumpy

spherule with a subrounded accretion (no. 1), a dark carbon

accretion (no. 2), and two hollow, magnetic spherules flattened by impact

(nos. 3 and 4). (B) Melrose: enlargement of box in A,

displaying fragmented impacting magnetic spherule (no. 1) forming a debris

ring (no. 2) that partially fused with the aluminosilicate host spherule. Fig. 9. Accretion textures. (A) Meteor Crater: glassy impactite with

multiple accretionary objects deformed by collisional impact (no. 1). (B) Talegasite:

cluster of large quenched spherules with smaller partially buried spherules

(no. 1), accretion spherules (no. 2), and accreted carbonaceous matter (no.

3). (C) Meteor Crater: accretion spherule on larger host with impact

pit lined with carbon (no. 1), quenched iron oxide surface crystals (light

dots at no. 2), and melt draping (no. 3). (D) Melrose: YDB

teardrop with a quench crust of aluminosilicate glass and a subcrust interior

of SiO2 and Al-rich glasses, displaying melt drapings (no. 1),

microcraters (no. 2), mullite crystals (no. 3), and accretion spherules (no.

4). YDB Objects by Site. Blackville, South Carolina. High-temperature melt products consisting of SLOs (420–2,700 μm)

and glassy spherules (15–1,940 μm) were collected at a depth of

1.75–1.9 m. SLOs range from small, angular, glassy, shard-like particles

to large clumps of highly vesiculated glasses, and may contain pockets of

partially melted sand, clay, mineral fragments, and carbonaceous matter.

Spherules range from solid to vesicular, and some are hollow with thin to

thick walls, and the assemblage also includes welded glassy spherules,

thermally processed clay clasts, and partially melted clays. Spherules show a considerable variation in composition and oxygen

fugacity, ranging from highly reduced, Al—Si-rich glasses to dendritic,

oxidized iron oxide masses. One Blackville spherule (Fig. 10A)

is composed of Al2O3-rich glasses set with lechatelierite, suessite, spheres of native

Fe, and quench crystallites of corundum and 2∶1 mullite, one of two stoichiometric forms of mullite (2Al2O3·SiO2, or 2∶1 mullite; and 3Al2O3·2SiO2, or 3∶2 mullite). This

spherule is an example of the most reduced melt with oxygen fugacity (fO2) along the IW (iron—wustite) buffer. Other highly oxidized objects

formed along the H or magnetite—hematite buffer. For example, one hollow

spherule contains 38% by volume of dendritic aluminous hematite (SI Appendix,

Fig. S16) with minor amounts of unidentified iron oxides set

in Fe-rich glass with no other crystallites. One Blackville SLO is composed

of high Al2O3–SiO2 glass with dendritic magnetite crystals and vesicles lined with

vapor-deposited magnetite (SI Appendix,

Fig. S17). In addition to crystallizing from the glass melt,

magnetite also crystallized contemporaneously with glassy carbon. These

latter samples represent the most oxidized of all objects, having formed

along the H or magnetite—hematite buffer, displaying 10-to 20-μm diameter

cohenite (Fe3C) spheres with inclusions of Fe

phosphide (Fe2P–Fe3P) containing up to 1.10 wt% Ni and 0.78 wt% Co. These occur in

the reduced zones of spherules and SLOs, some within tens of μm of

highly oxidized Al—hematite. These large variations in composition and oxygen

fugacity over short distances, which are also found in Trinity SLOs and

spherules, are the result of local temperature and physicochemical

heterogeneities in the impact plume. They are consistent with cosmic impacts,

but are inconsistent with geological and anthropogenic mechanisms. Fig. 10. SEM-BSE images of Blackville spherule. (A) Sectioned spherule

composed of high-temperature, vesiculated aluminosilicate glass and

displaying lechatelierite (no. 1) and reduced-Fe spherules (no. 2). (B)

False-colored enlargement of same spherule displaying lechatelierite (green,

no. 1) and reduced-Fe spherules (white, no. 2) with needle-like mullite

quench crystals (red, no. 3) and corundum quench crystals (red, no. 4). Spherules and SLOs from Blackville are mostly aluminosilicate glasses, as

shown in the ternary phase diagrams in SI Appendix, Fig. S9,

and most are depleted in K2O + Na2O, which may reflect high melting temperatures and concomitant loss of

volatile elements that increases the refractoriness of the melts. For most

spherules and SLOs, quench crystallites are limited to corundum and mullite,

although a few have the Fe—Al spinel, hercynite. These phases, together with

glass compositions, limit the compositional field to one with maximum

crystallization temperatures ranging from approximately 1,700–2,050 °C.

The spherule in Fig. 10A is

less alumina-rich, but contains suessite (Fe3Si), which indicates a crystallization temperature of

2,000–2,300 °C (13, 38). Observations of clay-melt interfaces with mullite or corundum-rich

enclaves indicate that the melt glasses are derived from materials enriched

in kaolinite with smaller amounts of quartz and iron oxides. Partially melted

clay discontinuously coated the surfaces of a few SLOs, after which mullite

needles grew across the clay—glass interface. The melt interface also has

quench crystals of magnetite set in Fe-poor and Fe-rich glasses (SI Appendix,

Fig. S18). SLOs also contain carbon-enriched black clay

clasts displaying a considerable range of thermal decomposition in concert

with increased vesiculation and vitrification of the clay host. The

interfaces between mullite-rich glass and thermally decomposed black clay

clasts are frequently decorated with suessite spherules. Abu Hureyra site, Syria. The YDB layer yielded abundant magnetic and glass spherules and SLOs

containing lechatelierite intermixed with CaO-rich glasses. Younger

layers contain few or none of those markers (SI Appendix,

Table S3). The SLOs are large, ranging in size up to

5.5 mm, and are highly vesiculated (SI Appendix,

Fig. S19); some are hollow and some form accretionary groups

of two or more objects. They are compositionally and morphologically similar

to melt glasses from Meteor Crater, which, like Abu Hureyra, is located

in Ca-rich terrain (SI Appendix,

Fig. S21). YDB magnetic spherules are smaller than at most

sites (20–50 μm). Lechatelierite is abundant in SLOs and exhibits

many forms, including sand-size grains and fibrous textured objects with

intercalated high-CaO glasses (Fig. 11).

This fibrous morphology, which has been observed in material from Meteor

Crater and Haughton Crater (SI Appendix,

Fig. S22), exhibits highly porous and vesiculated

lechatelierite textures, especially along planes of weakness that formed

during the shock compression and release stage. During impact, the SiO2 melted at very high post-shock temperatures

(> 2,200 °C), produced taffy-like stringers as the shocked rock

pulled apart during decompression, and formed many tiny vesicles from vapor

outgassing. We also observed distorted layers of hollow vesiculated silica

glass tube-like features, similar to some LDG samples (Fig. 12),

which are attributed to relic sedimentary bedding structures in the sandstone

precursor (39).

The Abu Hureyra tubular textures may be relic structures of

thin-bedded chert that occurs within the regional chalk deposits. These

clusters of aligned micron-sized tubes are morphologically unlike single,

centimeter-sized fulgurites, composed of melted glass tubes encased in unmelted sand.

The Abu Hureyra tubes are fully melted with no sediment coating,

consistent with having formed aerially, rather than below ground. Fig. 11. (A) Abu Hureyra: SLO (2 mm wide) with grey tabular

lechatelierite grains (no. 1) surrounded by tan CaO-rich melt (no. 2). (B)

SEM-BSE image showing fibrous lechatelierite (no. 1) and bubbled CaO-rich

melt (no. 2). Fig. 12. (A) Libyan Desert Glass (7 cm wide) displaying tubular glassy

texture (no. 1). (B) Abu Hureyra: lechatelierite tubes (no. 1)

disturbed by chaotic plastic flow and embedded in a vesicular, CaO-rich

matrix (no. 2). At Abu Hureyra, glass spherules have compositions comparable to

associated SLOs (SI Appendix,

Table S4) and show accretion and collision features similar

to those from other YDB sites. For example, low-velocity elliptical impact

pits were observed that formed by low-angle collisions during aerodynamic

rotation of a spherule (Fig. 13A).

The shape and low relief of the rims imply that the spherule was partially

molten during impact. It appears that these objects were splattered with

melt drapings while rotating within a debris cloud. Linear,

subparallel, high-SiO2 melt strands

(94 wt% SiO2) are mostly embedded within the high-CaO glass

host, but some display raised relief on the host surface, thus implying that

both were molten. An alternative explanation is that the strands are melt

relics of precursor silica similar tofibrous lechatelierite (Fig. 11). Fig. 13. Abu Hureyra: (A) SLO with low-angle impact craters (no. 1); half-formed

rims show highest relief in direction of impacts and/or are counter to

rotation of spherule. (B) Enlargement showing SiO2 glass strands (no. 1) on and in surface. Melrose site, Pennsylvania. As with other sites, the Melrose site displays exotic YDB carbon phases,

magnetic and glassy spherules, and coarse-grained SLOs up to 4 mm in

size. The SLOs exhibit accretion and collision features consistent with flash

melting and interactions within a debris cloud. Teardrop shapes are more

common at Melrose than at other sites, and one typical teardrop (Fig. 14 A and B)

displays high-temperature melt glass with mullite quench crystals on the

glassy crust and with corundum in the interior. This teardrop is highly

vesiculated and compositionally heterogeneous. FeO ranges from

15–30 wt%, SiO2 from 40–48 wt%,

and Al2O3 from 21–31 wt%. Longitudinally oriented flow lines suggest the

teardrop was molten during flight. These teardrops (Fig. 14 A–C)

are interpreted to have fallen where excavated because they are too fragile

to have been transported or reworked by alluvial or glacial processes. If an

airburst/impact created them, then these fragile materials suggest that the

event occurred near the sampling site. Fig. 14. Melrose. (A) Teardrop with aluminosilicate surface glass with

mullite quench crystals (no. 1) and impact pits (no. 2). (B) Sectioned

slide of Ashowing lechatelierite flow lines emanating from the

nose (Inset, no. 1), vesicles (no. 2), and patches of quenched

corundum and mullite crystals. The bright area (no. 3) is area with 30 wt% FeO compared

with 15 wt% in darker grey areas. (C) Reflected light

photomicrograph of C teardrop (Top) and SEM-BSE image

(Bottom) of teardrop that is compositionally homogeneous to A;

displays microcraters (no. 1) and flow marks (no. 2). (D) Melted

magnetite (no. 1) embedded in glass-like carbon. The magnetite interior is

composed of tiny droplets atop massive magnetite melt displaying flow lines

(no. 2). The rapidly quenched rim with flow lines appears splash formed (no.

3). Other unusual objects from the Melrose site are high-temperature

aluminosilicate spherules with partially melted accretion rims, reported for

Melrose in Wu (13),

displaying melting from the inside outward, in contrast to cosmic ablation

spherules that melt from the outside inward. This characteristic was also

observed in trinitite melt beads that have lechatelierite grains within the

interior bulk glasses and partially melted to unmelted quartz

grains embedded in the surfaces (22),

suggesting that the quartz grains accreted within the hot plume. The

heterogeneity of Melrose spherules, in combination with flow-oriented suessite and FeO droplets,

strongly suggests that the molten host spherules accreted a coating of bulk

sediment while rotating within the impact plume. The minimum temperature required to melt typical bulk sediment is

approximately 1,200 °C; however, for mullite and corundum solidus

phases, the minimum temperature is > 1,800°. The presence of suessite (Fe3Si) and reduced native Fe implies a minimum temperature of

> 2,000 °C, the requisite temperature to promote liquid flow in

aluminosilicate glass. Another high-temperature indicator is the presence of

embedded, melted magnetite (melting point, 1,550 °C) (Fig. 14D),

which is common in many SLOs and occurs as splash clumps on spherules at

Melrose (SI Appendix,

Fig. S23). In addition, lechatelierite is common in SLOs and

glass spherules from Melrose; the minimum temperature for producing schlieren

is > 2,000 °C. Trinity nuclear site, New Mexico. YDB objects are posited to have resulted from a cosmic airburst, similar

to ones that produced Australasian tektites, Libyan Desert Glass,

and Dakhleh Glass. Melted material from these sites is similar to

melt glass from an atomic detonation, even though, because of radioactive

materials, the means of surface heating is somewhat more complex (SI Appendix).

To evaluate a possible connection, we analyzed material from the Alamogordo

Bombing Range, where the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated in 1945.

Surface material at Trinity ground zero is mostly arkosic sand,

composed of quartz, feldspar, muscovite, actinolite, and iron oxides. The

detonation created a shallow crater (1.4 m deep and 80 m in

diameter) and melted surface sediments into small glass beads, teardrops, and

dumbbell-shaped glasses that were ejected hundreds of meters from ground zero

(Fig. 15A).

These objects rained onto the surface as molten droplets and rapidly

congealed into pancake-like glass puddles (SI Appendix,

Fig. S24). The top surface of this ejected trinitite is

bright to pale grey-green and mostly smooth; the interior typically is

heavily vesiculated (Fig. 17B).

Some of the glassy melt was transported in the rising cloud of hot gases and

dispersed as distal ejecta. Fig. 15. Trinity detonation. (A) Assortment of backlit, translucent

trinitite shapes: accretionary (no. 1), spherulitic (no. 2), broken teardrop

(no. 3), bottle-shaped (no. 4), dumbbell (no. 5), elongated or oval (no. 6).

(B) Edge-on view of a pancake trinitite with smooth top (no. 1),

vesiculated interior (no. 2), and dark bottom (no. 3) composed of partially

fused rounded trinitite objects incorporated with surface sediment. Fig. 17. Trinity: characteristics of high-temperature melting. (A) SEM-BSE

image of bead in trinitite that is mostly quenched, dendritic magnetite (no.

1). (B) Melt beads of native Fe in etched glass (no. 1). (C)

Heavily pitted head of a trinitite teardrop (no. 1) resulting from collisions

in the debris cloud. Temperatures at the interface between surface minerals and the puddled,

molten trinitite can be estimated from the melting behavior of quartz grains

and K-feldspar that adhered to the molten glass upon impact with the ground (SI Appendix,

Fig. S22). Some quartz grains were only partly melted,

whereas most other quartz was transformed into lechatelierite (26).

Similarly, the K-feldspar experienced partial to complete melting. These

observations set the temperature range from 1,250 °C (complete melting

of K-feldspar) to > 1,730 °C (onset of quartz melting).

Trinitite samples exhibit the same high-temperature features as observed in

materials from hard impacts, known airbursts, and the YDB layer. These

include production of lechatelierite from quartz (T = 1,730–2,200 °C),

melting of magnetite and ilmenite to form quench textures (T≥1,550 °C),

reduction of Fe to form native Fe spherules, and extensive flow features in

bulk melts and lechatelierite grains (Fig. 16).

The presence of quenched magnetite and native iron spherules in trinitite

strongly suggests extreme oxygen fugacity conditions over very short

distances (Fig. 17B);

similar objects were observed in Blackville SLOs (Fig. 10A).

Other features common to trinitite and YDB objects include accretion of

spherules/beads on larger objects, impact microcratering, and melt

draping (Figs. 16 and 17). Fig. 16. Trinitite produced by debris cloud interactions. (A) Trinitite

spherule showing accreted glass bead with impact pits (no. 1); melt drapings (no.

2); and embedded partially melted quartz grain (no. 3), carbon filament (no.

4), and melted magnetite grain (no. 5). (B) Enlarged image of box

in A showing melt drapings (no. 1), and embedded

partially melted quartz grain (no. 2) and melted magnetite grains (no. 3).

See Fig. 9Dfor

similar YDB melt drapings. The Trinity nuclear event, a high-energy airburst, produced a wide range

of melt products that are morphologically indistinguishable from YDB objects

that are inferred to have formed during a high-energy airburst (SI Appendix,

Table S1). In addition, those materials are morphologically

indistinguishable from melt products from other proposed cosmic airbursts,

including Australasian tektites, Dakhleh Glass, and Tunguska

spherules and glass. All this suggests similar formation mechanisms for the

melt materials observed in of these high-energy events. Methods YDB objects were extracted by 15 individuals at 12 different

institutions, using a detailed protocol described in Firestone et al. (1)

and Israde-Alcántara et al. (4).

Using a neodymium magnet (5.15 × 2.5 × 1.3 cm; grade

N52 NdFeB; magnetization vector along 2.5-cm face; surface field

density = 0.4 T; pull force = 428 N) tightly

wrapped in a 4-mil plastic bag, the magnetic grain fraction (dominantly

magnetite) was extracted from slurries of 300–500 g bulk sediment and

then dried. Next, the magnetic fraction was sorted into multiple size

fractions using a stack of ASTM sieves ranging from 850–38 μm.

Aliquots of each size fraction were examined using a 300× reflected light

microscope to identify candidate spherules and to acquire photomicrographs (Fig. 1),

after which candidate spherules were manually selected, tallied, and

transferred to SEM mounts. SEM-EDS analysis of the candidate spherules

enabled identification of spherules formed through cosmic impact compared

with terrestrial grains of detrital and framboidal origin. From the magnetic

fractions, SLO candidates > 250 μm were identified and

separated manually using a light microscope from dry-sieved aliquots and

weighed to provide abundance estimates. Twelve researchers at 11 different

universities acquired SEM images and obtained > 410 analyses.

Compositions of YDB objects were determined using standard procedures for

SEM-EDS, electron microprobe, INAA, and PGAA. Conclusions Abundance peaks in SLOs were observed in the YDB layer at three dated

sites at the onset of the YD cooling episode (12.9 ka). Two are in North

America and one is in the Middle East, extending the existence of YDB proxies

into Asia. SLO peaks are coincident with peaks in glassy and Fe-rich

spherules and are coeval with YDB spherule peaks at 15 other sites across

three continents. In addition, independent researchers working at one

well-dated site in North America (8)

and one in South America (10⇓–12)

have reported YDB melt glass that is similar to these SLOs. YDB objects have

now been observed in a total of eight countries on four continents separated

by up to 12,000 km with no known limit in extent. The following lines of

evidence support a cosmic impact origin for these materials. Geochemistry. Our research demonstrates that YDB spherules and SLOs have

compositions similar to known high-temperature, impact-produced

material, including tektites and ejecta. In addition, YDB objects are

indistinguishable from high-temperature melt products formed in the Trinity

atomic explosion. Furthermore, bulk compositions of YDB objects are

inconsistent with known cosmic, anthropogenic, authigenic, and volcanic

materials, whereas they are consistent with intense heating, mixing, and

quenching of local terrestrial materials (mud, silt, clay, shale). Morphology. Dendritic texturing of Fe-rich spherules and some SLOs resulted from

rapid quenching of molten material. Requisite temperatures eliminate

terrestrial explanations for the 12.9-kyr-old material (e.g., framboids and

detrital magnetite), which show no evidence of melting. The age,

geochemistry, and morphology of SLOs are similar across two continents,

consistent with the hypothesis that the SLOs formed during a cosmic impact

event involving multiple impactors across a wide area of the Earth. Lechatelierite and Schlieren. Melting of SLOs, some of which are > 80% SiO2 with pure SiO2 inclusions, requires

temperatures from 1,700–2,200 °C to produce the distinctive flow-melt

bands. These features are only consistent with a cosmic impact event and

preclude all known terrestrial processes, including volcanism, bacterial

activity, authigenesis, contact metamorphism, wildfires, and coal seam

fires. Depths of burial to 14 m eliminate modern anthropogenic

activities as potential sources, and the extremely high melting temperatures

of up to 2,200 °C preclude anthropogenic activities (e.g., pottery-making,

glass-making, and metal-smelting) by the contemporary cultures. Microcratering. The YDB objects display evidence of microcratering and

destructive collisions, which, because of the high initial and differential

velocities required, form only during cosmic impact events and nuclear

explosions. Such features do not result from anthropogenesis or volcanism. Summary. Our observations indicate that YDB objects are similar to material

produced in nuclear airbursts, impact crater plumes, and cosmic airbursts,

and strongly support the hypothesis of multiple cosmic airburst/impacts at

12.9 ka. Data presented here require that thermal radiation from air

shocks was sufficient to melt surface sediments at temperatures up to or

greater than the boiling point of quartz (2,200 °C). For impacting

cosmic fragments, larger melt masses tend to be produced by impactors with

greater mass, velocity, and/or closeness to the surface. Of the 18 investigated

sites, only Abu Hureyra, Blackville, and Melrose display large melt

masses of SLOs, and this observation suggests that each of these sites was

near the center of a high-energy airburst/impact. Because these three sites

in North America and the Middle East are separated by 1,000–10,000 km,

we propose that there were three or more major impact/airburst epicenters for

the YDB impact event. If so, the much higher concentration of SLOs at

Abu Hureyra suggests that the effects on that settlement and its

inhabitants would have been severe. Acknowledgments We thank Malcolm LeCompte, Scott Harris, Yvonne Malinowski,

Paula Zitzelberger, and Lawrence Edge for providing crucial samples,

data, and other assistance; and Anthony Irving, Richard Grieve, and two anonymous

reviewers for useful reviews and comments on this paper. This research was

supported in part by US Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 and

US National Science Foundation Grant 9986999 (to R.B.F.); US National Science

Foundation Grants ATM-0713769 and OCE-0825322, Marine Geology and Geophysics

(to J.P.K.); US National Science Foundation Grant OCD-0244201 (to D.J.K.);

and US National Science Foundation Grant EAR-0609609, Geophysics (to G.K.).

Very

high-temperature impact melt products as evidence for cosmic airbursts and

impacts 12,900 years ago Ted E. Bunch, Robert E. Hermes, Andrew M.T. Moore, Douglas J. Kennett,

James C. Weaver, James H. Wittke, Paul S. DeCarli, James L.

Bischoff, Gordon C. Hillman, George A. Howard, David R. Kimbel,

Gunther Kletetschka, Carl P. Lipo, Sachiko Sakai, Zsolt Revay,

Allen West, Richard B. Firestone, and James P. Kennett PNAS July 10, 2012. 109 (28) E1903-E1912; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1204453109 Abstract It has been proposed that fragments of an asteroid or comet impacted

Earth, deposited silica-and iron-rich microspherules and other

proxies across several continents, and triggered the Younger Dryas

cooling episode 12,900 years ago. Although many independent groups have

confirmed the impact evidence, the hypothesis remains controversial because

some groups have failed to do so. We examined sediment sequences from 18 dated

Younger Dryas boundary (YDB) sites across three continents (North America,

Europe, and Asia), spanning 12,000 km around nearly one-third of the

planet. All sites display abundant microspherules in the YDB with

none or few above and below. In addition, three sites (Abu Hureyra,

Syria; Melrose, Pennsylvania; and Blackville, South Carolina) display

vesicular, high-temperature, siliceous scoria-like objects, or SLOs, that

match the spherules geochemically. We compared YDB objects with melt products

from a known cosmic impact (Meteor Crater, Arizona) and from the 1945 Trinity

nuclear airburst in Socorro, New Mexico, and found that all of these

high-energy events produced material that is geochemically and

morphologically comparable, including: (i) high-temperature, rapidly

quenched microspherules and SLOs; (ii) corundum, mullite,

and suessite (Fe3Si), a rare meteoritic

mineral that forms under high temperatures; (iii) melted SiO2 glass, or lechatelierite, with flow textures (or schlieren) that

form at > 2,200 °C; and (iv) particles with features

indicative of high-energy interparticle collisions. These results are

inconsistent with anthropogenic, volcanic, authigenic, and cosmic materials,

yet consistent with cosmic ejecta, supporting the hypothesis of extraterrestrial

airbursts/impacts 12,900 years ago. The wide geographic distribution of

SLOs is consistent with multiple impactors. · tektite · microcraters · oxygen fugacity · trinitite Manuscript Text The discovery of anomalous materials in a thin sedimentary layer up to a

few cm thick and broadly distributed across several continents led Firestone

et al. (1)

to propose that a cosmic impact (note that “impact” denotes a collision by a

cosmic object either with Earth’s surface, producing a crater, or with its

atmosphere, producing an airburst) occurred at 12.9 kiloannum (ka;

all dates are in calendar or calibrated ka, unless otherwise indicated) near

the onset of the Younger Dryas (YD) cooling episode. This stratum, called the

YD boundary layer, or YDB, often occurs directly beneath an organic-rich

layer, referred to as a black mat (2),

that is distributed widely over North America and parts of South America,

Europe, and Syria. Black mats also occur less frequently in quaternary

deposits that are younger and older than 12.9 ka (2).

The YDB layer contains elevated abundances of iron- and silica-rich microspherules (collectively

called “spherules”) that are interpreted to have originated by cosmic impact

because of their unique properties, as discussed below. Other markers include

sediment and magnetic grains with elevated iridium concentrations and exotic

carbon forms, such as nanodiamonds, glass-like carbon, aciniform soot,

fullerenes, carbon onions, and carbon spherules (3, 4).

The Greenland Ice Sheet also contains high concentrations of atmospheric

ammonium and nitrates at 12.9 ka, indicative of biomass burning at the

YD onset and/or high-temperature, impact-related chemical synthesis (5).

Although these proxies are not unique to the YDB layer, the combined

assemblage is highly unusual because these YDB markers are typically present

in abundances that are substantially above background, and the assemblage

serves as a datum layer for the YD onset at 12.9 ka. The wide range of

proxies is considered here to represent evidence for a cosmic impact that

caused airbursts/impacts (the YDB event may have produced ground impacts and

atmospheric airbursts) across several continents. Since the publication of Firestone et al. (1),

numerous independent researchers have undertaken to replicate the results.

Two groups were unable to confirm YDB peaks in spherules (6, 7),

whereas seven other groups have confirmed them (*, †, ‡, 8⇓⇓⇓⇓⇓–14),

with most but not all agreeing that their evidence is consistent with a

cosmic impact. Of these workers, Fayek et al. (8)

initially observed nonspherulitic melted glass in the well-dated

YDB layer at Murray Springs, Arizona, reporting “iron oxide spherules

(framboids) in a glassy iron–silica matrix, which is one indicator of a

possible meteorite impact…. Such a high formation temperature is only

consistent with impact… conditions.” Similar materials were found in the YDB

layer in Venezuela by Mahaney et al. (12),

who observed “welded microspherules,… brecciated/impacted quartz and

feldspar grains, fused metallic Fe and Al, and… aluminosilicate glass,” all

of which are consistent with a cosmic impact. Proxies in High-Temperature Impact Plumes. Firestone et al. (1)

proposed that YDB microspherules resulted from ablation of the

impactor and/or from high-temperature, impact-related melting of terrestrial

target rocks. In this paper, we explore evidence for the latter possibility.

Such an extraterrestrial (ET) impact event produces a turbulent impact plume

or fireball cloud containing vapor, melted rock, shocked and unshocked rock

debris, breccias, microspherules, and other target and impactor

materials. One of the most prominent impact materials is melted siliceous

glass (lechatelierite), which forms within the impact plume at temperatures

of up to 2,200 °C, the boiling point of quartz. Lechatelierite cannot

be produced volcanically, but can form during lightning strikes as

distinctive melt products called fulgurites that typically have unique

tubular morphologies (15).

It is also common in cratering events, such as Meteor Crater, AZ (16),

and Haughton Crater, Canada§, as well as in probable high-temperature aerial

bursts that produced melt rocks, such as Australasian tektites (17),

Libyan Desert Glass (LDG) (17), Dakhleh Glass

(18),

and potential, but unconfirmed, melt glass from Tunguska, Siberia (19).

Similar lechatelierite-rich material formed in the Trinity nuclear

detonation, in which surface materials were drawn up and melted within the

plume (20). After the formation of an impact fireball, convective cells form at

temperatures higher than at the surface of the sun (> 4,700 °C),

and materials in these cells interact during the short lifetime of the plume.

Some cells will contain solidified or still-plastic impactites, whereas in

other cells, the material remains molten. Some impactites are rapidly ejected

from the plume to form proximal and distal ejecta depending on their mass and

velocity, whereas others are drawn into the denser parts of the plume, where

they may collide repeatedly, producing multiple accretionary and collisional

features. Some features, such as microcraters, are unique to impacts and

cosmic ablation and do not result from volcanic or anthropogenic processes¶. For ground impacts, such as Meteor Crater (16),

most melting occurred during the formation of the crater. Some of the molten

rock was ejected at high angles, subsequently interacting with the rising hot

gas/particulate cloud. Most of this material ultimately fell back onto the

rim as proximal ejecta, and molten material ejected at lower angles became

distal ejecta. Cosmic impacts also include atmospheric impacts called

airbursts, which produce some material that is similar to that

produced in a ground impact. Aerial bursts differ from ground impacts in that

mechanically shocked rocks are not formed, and impact markers are primarily

limited to materials melted on the surface or within the plume. Glassy

spherules and angular melted objects also are produced by the hot

hypervelocity jet descending to the ground from the atmospheric explosion.

The coupling of the airburst fireball with the upper soil layer of Earth’s

surface causes major melting of material to a depth of a few cm. Svetsov and

Wasson (2007) ∥ calculated

that the thickness of the melted layer was a function of time and flux

density, so that for Te > 4,700 °C

at a duration of several seconds, the thickness of melt is 1–1.5 cm.

Calculations show that for higher fluxes, more soil is melted, forming

thicker layers, as exemplified by Australasian tektite layered melts. The results of an aerial detonation of an atomic bomb are similar to

those of a cosmic airburst (e.g., lofting, mixing, collisions, and

entrainment), although the method of heating is somewhat different because of

radioactive byproducts (SI Appendix).

The first atomic airburst occurred atop a 30-m tower at the Alamogordo

Bombing Range, New Mexico, in 1945, and on detonation, the thermal blast wave

melted 1–3 cm of the desert soils up to approximately 150 m in

radius. The blast did not form a typical impact-type crater; instead, the

shock wave excavated a shallow depression 1.4 m deep and 80 m in

diameter, lifting molten and unmelted material into the rising, hot

detonation plume. Other melted material was ejected at lower angles, forming

distal ejecta. For Trinity, Hermes and Strickfaden (20)

estimated an average plume temperature of 8,000 °C at a duration of

3 s and an energy yield of up to 18 kilotons (kt) trinitrotoluene

(TNT) equivalent. Fallback of the molten material, referred to as trinitite,

littered the surface for a diameter of 600 m, in some places forming

green glass puddles (similar to Australasian layered tektites). The

ejecta includes irregularly shaped fragments and aerodynamically shaped

teardrops, beads, and dumbbell glasses, many of which show collision and

accretion features resulting from interactions in the plume (similar to Australasian

splash-form tektites). These results are identical to those from known cosmic

airbursts. SI Appendix,

Table S1 provide a comparison of YDB objects with impact

products from Meteor Crater, the Australasian tektite field, and the Trinity

nuclear airburst. Scope of Study. We investigated YDB markers at 18 dated sites, spanning 12,000 km

across seven countries on three continents (SI Appendix, Fig. S1),

greatly expanding the extent of the YDB marker field beyond earlier studies (1).

Currently, there are no known limits to the field. Using both deductive and

inductive approaches, we searched for and analyzed YDB spherules and melted

siliceous glass, called scoria-like objects (SLOs), both referred to below as

YDB objects. The YDB layer at all 18 sites contains microspherules, but

SLOs were found at only three sites: Blackville, South Carolina; Abu Hureyra,

Syria; and Melrose, Pennsylvania. Here, we focus primarily on abundances,

morphology, and geochemistry of the YDB SLOs. Secondarily, we discuss

YDB microspherules with regard to their geochemical similarity

and co-occurrence with SLOs. We also compare compositions of YDB objects to

compositions: (i) of materials resulting from meteoritic ablation and

from terrestrial processes, such as volcanism, anthropogenesis, and

geological processes; and (ii) from Meteor Crater, the Trinity nuclear

detonation, and four ET aerial bursts at Tunguska, Siberia; Dakhleh Oasis,

Egypt; Libyan Desert Glass Field, Egypt; and the Australasian tektite strewnfield,

SE Asia. For any investigation into the origin of YDB objects, the question arises

as to whether these objects formed by cosmic impact or by some other process.

This is crucial, because sedimentary spherules are found throughout the

geological record and can result from nonimpact processes, such as cosmic

influx, meteoritic ablation, anthropogenesis, lightning, and volcanism.

However, although microspherules with widely varying origins can

appear superficially similar, their origins may be determined with reasonably

high confidence by a combination of various analyses—e.g., scanning electron

microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and

wavelength-dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) by electron microprobe—to examine

evidence for microcratering, dendritic surface patterns produced during

rapid melting—quenching **, and

geochemical composition. Results and discussion are below and in the SI Appendix. SLOs at YDB Sites. Abu Hureyra, Syria. This is one of a few archaeological sites that record the transition from

nomadic hunter—gatherers to farmer—hunters living in permanent villages (21).

Occupied from the late Epipalaeolithic through the Early Neolithic

(13.4–7.5 ka), the site is located close to the Euphrates River on

well-developed, highly calcareous soils containing platy flint (chert)

fragments, and the regional valley sides are composed of chalk with thin beds

of very fine-grained flint. The dominant lithology is limestone within a few

km, whereas gypsum deposits are prominent 40 km away, and basalt is

found 80 km distant. Much of this part of northern Syria consists of

highly calcareous Mediterranean, steppe, and desert soils. To the east of

Abu Hureyra, there are desert soils marked by wind-polished flint

fragments forming a pediment on top of marls (calcareous and clayey

mudstones). Thus, surface sediments and rocks of the entire region are

enriched in CaO and SiO2. Moore and co-workers

excavated the site in 1972 and 1973, and obtained 13 radiocarbon dates

ranging from 13.37 ± 0.30 to 9.26 ± 0.13 cal ka

B.P., including five that ranged from 13.04 ± 0.15 to

12.78 ± 0.14 ka, crossing the YDB interval (21)

(SI Appendix,

Table S2). Linear interpolation places the date of the YDB